Secure E-voting by Another Name: Vote-by-Mail

by caliber | October 26, 2020

A data-security perspective on why casting a ballot by mail is more secure than voting in person, and how the Washington State system has potential to be even stronger

2020 is a year for the ages. Despite the ravages of the SARS-2 Coronavirus and the doldrums of the economy, election season is now in full swing. Wherever you sit on the political spectrum, one of the stranger controversies besetting the United States is over the US Mail system and systems where citizens in various states vote by mail.

In every state there is a vote-by-mail system that has been in place for years: absentee balloting. Strangely, a controversy has erupted around extended use of the same system as absentee ballots, whereby a majority or the entire election is conducted using the same mechanisms.

From a data security perspective, there are some interesting issues with different implementations of vote-by-mail, particularly those that intersect with notions of “E-voting”, where the ballots themselves are technologically advanced, but the transport mechanism is a postal carrier. At Caliber Security, we have an up-close view of the system that is in place in Washington State.

How we do (electronic) voting by mail

Authorizing the vote

We start with an eligible voter who provides a valid address that they assert is a place they can receive their ballot. (Voter registration must be accurate according to the rules of the state in which it’s implemented. One has to satisfy the requirements for residence, and we make an assumption that a good system is in place, with some checks and balances. We’re not going to explore that here.)

The address is usually a personal residence, but since there’s no requirement that a person own property in order to vote, it may also be a mailbox for someone who works on Alaskan fishing boats part of the time, a work address for someone who lives in temporary housing, or the marina address for someone who lives on their boat. Once a person has proved they are a citizen and a valid state resident, it’s their choice where they choose to receive their ballot.

How ballots are sent

The state examines, authorizes, and verifies each voter registration. Any attempts at duplicate registration or registration of false people are handled through normal means, the same as they have been for decades past. There’s no real opportunity for fraud or misuse different from any other system. Once the office of voter registration completes that process, a ballot is mailed using the USPS to the address specified by the qualified voter, a few weeks prior to each election. Using the USPS ensures that the ballots are carried by federal employees (though technically working for a federal public corporation), and fully subject to federal law, procedures, and penalties for interception based on Article 1, Section 8 of the US Constitution (a far more stringent standard than volunteers handing out ballots and manning voting booths in the local community center).

What the voter receives

Each voter receives a sealed envelope, with no identifying information other than the recipient’s name and address (no party affiliation or other disclosures), and some stern admonishments that it is only to be opened by the specified addressee. This is no different than any other first-class mail containing a paycheck or tax forms. Stealing, opening, or otherwise impeding the letter getting to the addressee is a federal crime.

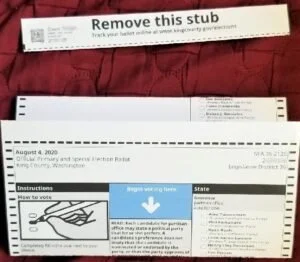

What we find inside the envelope consists of a ballot, some instructions, and the necessary covers and envelopes to securely return the ballot.

How to vote

Here’s a small twist that escapes a lot of discussions around voting by mail: the ballot is a machine-readable answer sheet, same as the iconic Scantron(™) or McGraw-Hill bubble forms used for standardized tests. As soon as the voter fills out the machine-readable ballot, it is essentially a piece of data ready to be transmitted, counted, verified, and archived for future error correction or any audit that might be needed. As with any other form, the voter needs to fill in each bubble completely and clearly, in order to express a valid vote.

One bit of trouble one must account for… is when 32 people run for governor it may be a bit daunting to find your preferred candidate among the Seafair Pirates promising to fill all potholes with fruitcake after the holiday season, and the guy whose response to the question asking whether he does any community service was “I’ve never been to jail.” On the other hand, if the ballot requires a drink or two just to get through it, it’s nice to be able to do so in the comfort of one’s home.

Authenticating the ballot

Once the voting (and exasperated sighs) are done, the ballot needs to be authenticated before submission. A signature suffices, but this piece of authentication is placed on the envelope after the ballot is filled out, not the machine readable ballot itself. In this way the votes contained on the ballot remain anonymous, but the ballot has a barcode that matches the authorization comprising the outbound envelope to the registered voter, and the signed inbound envelope matches the voter registration records and can be verified. Thus there’s a full loop, and the outbound authorization is tied to inbound authentication without disclosing how anyone voted.

A little piece of non-repudiation

The voter tears off the tab from the top edge of the ballot, which contains the ballot barcode and information indicating the election for which it will be cast. By keeping this tab, the voter keeps a record of what they sent, which is useful for verification and/or non-repudiation of the ballot and its votes… but more on that later.

Securing each ballot

Each complete ballot is then placed inside the prepared return envelope. In the Washington State system, there is also an optional security folder the voter can place the ballot into, to further strengthen the privacy of the ballot, as it is being returned.

The return envelope is then sealed, and the voter signs the outside of the sealed envelope — which must match the voter registration.

A little note on declaring a party affiliation

As has been hyped with uninformed hand-wringing, some ballots require a party affiliation to be declared on the outside envelope — and this has been a source of much political controversy. However, it is important to stress this is never the case in a general election. The only point at which a party affiliation is required on the outside of a ballot is for primaries in which a voter must indicate which election they are voting in.

No party affiliation declaration is ever required for a general election. When Washington State ended the “Open Primary” system (in which a voter registered as member of one party could abuse the system to vote for a least-favorable person of the opposing party, thereby monkey-wrenching other parties’ primaries), the declaration was instituted to ensure that people were voting in the correct primary election for which they had registered.

Transmitting the ballot back to the state

Some people choose to drop the ballot back into the mail, using the same verified USPS transport process described above. If it’s good enough for taxes and legal notices….

Here, though, we always have the option to drop the ballot into secure ballot boxes controlled by the state elections board. For example, this ballot box is permanently installed outside the local library, one of 450 ballot boxes across Washington state. They’re stronger and heavier than a dumpster, weatherproof and immovable, resistant to vandalism, and have tamper-proof seals to track every time they’re opened.

During election season, the ballot box slot is opened for people to drop off their ballots anytime. The ballots are picked up from each ballot box by sworn and certified county elections officials, with two present at all times. Each time the box is opened, the ballots are sealed in a locked container, which is logged to the tamper seal on the box. Each batch is then transported back to the tabulation center — and a duplicate of the box, container, and transport log is kept inside the container so that it can be verified upon receipt. No one person can access any ballot or tamper with the batches without leaving immediately-obvious evidence.

Validating the ballot

By the time election day rolls around, the vast majority of ballots will have already been returned to a tabulation center, pulled from their envelopes, collated into clean processable batches, and ready to read. This is where things get faster and more efficient. Early voters’ ballots can be queued up and validated against registration records with or without performing an early count. Any legibility problems, invalid ballots, or other issues can be readily identified — and re-examined as many times as necessary to identify any systemic issues.

Tallying and verifying votes

The forms are scanned using vendor systems that have been certified to return accurate results of the paper forms. There is no obscured, encrypted, or otherwise-unavailable data, so the forms can be re-scanned if there’s an issue, or scanned using alternate equipment to validate the tallies. Unlike touch-screen voting systems, a hybrid electronic-vote-by-mail system can be verified at every step because there is an obvious and clear storage medium for the data.

There is no situation in which a vote can be thrown out without a traceable record back to the voter, and there’s no situation in which an unreadable or troublesome ballot can’t be audited and manually examined by elections officials. Because the voting record itself is stored on effectively-open-source storage media (paper with human- and machine-readable choices), the tallying system itself could even be verified by running the same ballots through different scanning systems, even if the tabulation code were not available for review.

Strengths of mail-in e-voting, and potential failures or vulnerabilities

Mail-in voting that uses ballots that are both machine- and human-readable provides several strengths:

Accuracy – Marked forms are open and clearly readable

Recounts – ballot recounting is automatable with alternate methods

Resistance to tampering – from registration to collection, the methods are as secure as in-person

Retention and durability – paper recording of machine-readable data has a shelf life exceeding a century

On the other hand, some potential weaknesses or vulnerabilities should be accounted for as well:

Forged registration – the risks of forged registration are the same as other voting methods

Stolen ballots – stolen ballots are serialized and traceable if used

Miscounts – machine errors in counting are no higher risk than all other methods

Overvotes and undervotes – machine tampering to produce over- or under-votes are hard to hide if they occur

Determining the actual and practical risks of a hybrid-style voting system is dependent on error-checking over all other principles. Knowing when there’s been an error — even if the error itself is unknown and needs to be investigated — is the first step in all cases. So far, experience tells us that this system meets the challenges by including:

Ballots that are human- and machine- readable

Auditability by hand and by machine

Auditability and error detection not dependent on closed code

Primary data storage (paper ballot) has a long shelf life

The political controversy surrounding absentee ballots, remote voting, vote by mail, or other methods; these just aren’t supported by evidence. Voter fraud in the United States is vanishingly rare, and has never come anywhere close to making a difference in any recorded election. In a recent sample of a half dozen years in Washington State, there were only 14 cases of improper, duplicate, or fraudulent votes in 10 million, and only half of those (7) met the minimum bar for legal action.

If we consider that an error rate, it’s just 0.0007%. For context, the NYU School of Law (numbers from the Brennan Center for Justice) calculates the average rate of error or fraud in the United States as historically between 0.0003% and 0.0025%. That’s more than a decade operating well below the average problem rates, with no real emergent change or risk.

Even more critical in the current context, a hybrid vote-by-mail approach is exactly what was needed when the COVID-19 pandemic spread throughout the nation. Serendipitous or not, it was and remains the right solution for the situation, allowing us to continue as a functional democracy without undue risk to the health of the citizenry.

What the future holds: Hash the Vote

Maintaining and restoring trust in a democratic system depends both on secure voting methods that satisfy the demands of the past to remain open and auditable, and the demands of the future to be accessible and internet-enabled. Hybrid approaches like the one implemented in Washington have been successful so far, and appear well-positioned and durable to survive future demands.

For example, one of the high-potential demands might be to provide voters with confirmation not only that their ballot was received, but that each vote was counted correctly. Using the existing platform with a carefully implemented hashing of each vote number and response along with the ballot identifier could provide this — and it’s the most likely next step. We look forward to it.